Love in the Rohingya Camps

I became a refugee in 1992, when I was a toddler. My family fled during one of the many expulsions of the Rohingya people from Myanmar. I basically grew up in Bangladesh. I speak my own language but I also read and write Bangla, and speak it fluently. The similarity with other Bangladeshis ends there. I live confined. I live according to a variety of rules. I live within barbed wire. There are many restrictions and limits for us Rohingya.

Being a refugee is like a series of negotiations where you really don’t have much power or ability to negotiate. So you always come off badly in any negotiation. I can’t even say that we compromise. Compromise suggests that we have some degree of influence. We don’t. We simply accept. We are expected to accept. And we do. Most of the time.

We complain sometimes. We feel outrage. And then we are cowed. We often ask ourselves, “Do the things that happen to us outrage the world?” We never get a clear answer. And so for many of us, silence has become a way of life. This is how we deal with the daily injustices and this is how we surface our pain and even our rage.

Like many people, how I fell in love for the first time was very difficult. In fact, I would say it was traumatic. It was the usual difficulties involving acceptance by each other’s families. How I overcame the difficulties and eventually married the love of my life has been instructive. And I believe it will remain a singular lesson for all my life.

I was not going to be cowed. I was not going to compromise. I was not going to stay silent. I was not going to do nothing. Indeed I did everything in my power to marry her. And I did. I have not regretted it.

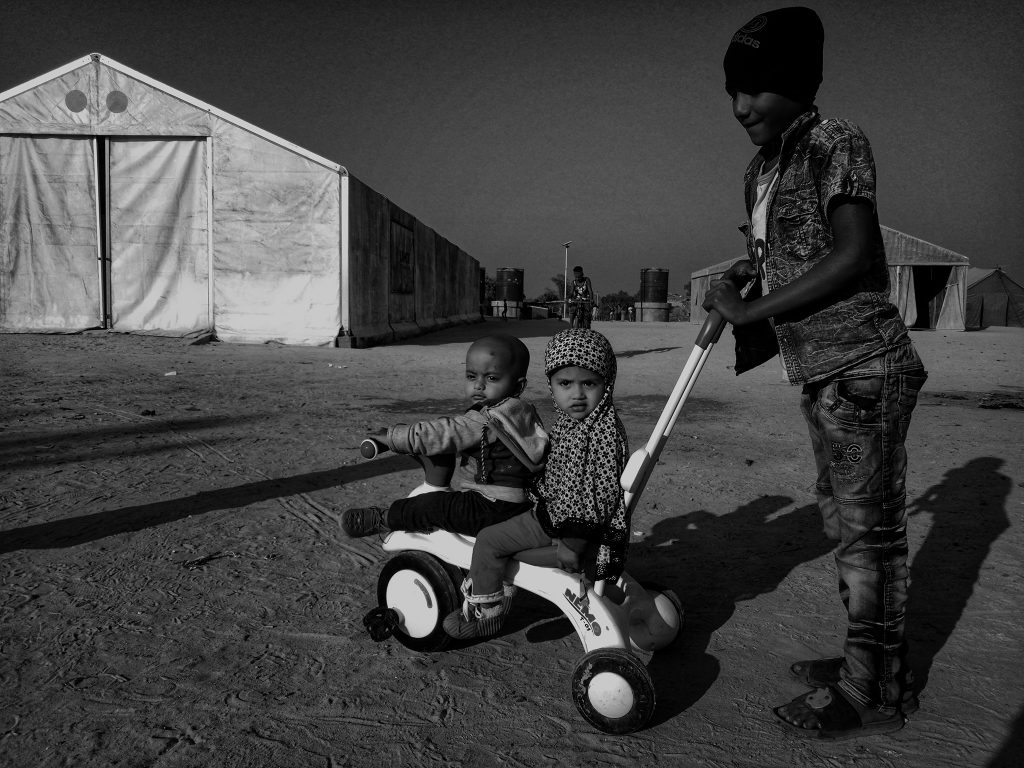

In my photography, the theme of love is important. I think more than anything else, I need to capture moments which speak of love. These moments of personal love I hope will translate somewhere, someday, into a more universal love for the freedom we refugees seek.

Salim Ullah Armany is a 32-year-old Rohingya refugee from Buthidaung, Myanmar. He lives in Kutupalong in Bangladesh – the world’s largest refugee camp. Salim’s photography is predominantly black-and-white. One of his aims, he says, is to show that “refugees have many aspirations, and these are no different from the aspirations of people who are not refugees.” See more of Salim’s work on Instagram.

This collaboration with The Unheard Project was made possible by Shafiur Rahman of Doc Sábbá and @RohingyaPhotography. You can find him on Twitter @shafiur as well as his Website.