In Conversation: Hangama Amiri

Hangama Amiri is an Afghan-Canadian artist who holds an MFA from Yale University, where she graduated in 2020 from the Painting and Printmaking Department. She received her BFA from NSCAD University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and is a Canadian Fulbright and Post-Graduate Fellow at Yale University School of Art and Sciences (2015-2016). Her work is exhibited nationally and internationally in New York City, Toronto, France, Italy, London (UK), and Sofia, Bulgaria. She has won the 2011 Lieutenant Governor’s Community Volunteerism Award, and the 2013 Portia White Protege Award, and in 2015, her painting Island of Dreams won a runner-up honourable mention at RBC Canadian Painting Competition.

Amiri was also an artist-in-residence at the Banff Centre for Arts & Creativity (Fall 2017), Joya AiR Residency Program in Almería, Andalucía, Spain (Winter 2017), World of CO Residency program in Sofia, Bulgaria (Spring 2018), and at Long Road Projects in Jacksonville, Florida (Summer 2019).

This interview was conducted via Zoom between Singapore and Amiri’s current residence in New Haven, Connecticut.

THE UNHEARD PROJECT: Going by your official CV you’re now 10 years into an incredible career that began with “The Wind-up Dolls of Kabul” in 2012. But because memory, childhood and home have always been core concepts to your work, it actually sounds like your relationship with art might have begun much earlier.

Hangama Amiri: My relationship to art started from a very young age, when my family first began migrating. I was only in grade 1 when the Taliban took over Afghanistan in 1996 and we became refugees in Pakistan. It was here where I would pick up a pencil and start drawing things I saw in my dreams, or whatever I saw in front of me.

One of my cousins in Pakistan went to art school, so I would go to his studio – which was in a small basement – and watch him make these beautiful figurative drawings out of charcoal. Sometimes he would draw nude figures and hide them from his mom [laughs] but because we kids had access to that space, it was fascinating just being there and watching him make work. I loved it. So I kept drawing, using pencils and colour pencils, before slowly introducing myself to painting. I became very serious about it, even at 13 years old.

Was art well-received in the family?

My cousin was male, so he had that support and praise with what he wanted to do as an artist. But there weren’t any female artists in my family growing up. Artists are thought to be very spiritually free people, very adventurous. But my parents were working-class, and having a daughter who felt the same – who didn’t think about the future but wanted to follow her passions – was hard for them to accept. Being an artist was something that was difficult to take seriously, in comparison to other occupations like doctors or nurses. It was a rough path, to be honest. It took me a long time, and it took them a long time to comprehend what I was doing with my life. But they’re really proud of me now, and they believe in me. It’s a great feeling.

You’ve been studying fine art formally since college – first in Tajikistan, then in Nova Scotia, and then as a Fulbright scholar at Yale, where you graduated in 2020 with an MFA from the Painting and Printmaking Department. What were some of the pros and cons of being in a school system? What would you have done differently or what would you have done over and over, happily?

When I was in 13 and living in Tajikistan, organisations like UNHCR and UNICEF would run creative workshops for refugees. The first prize for one of them was a scholarship to a two-year college degree. I did a drawing of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, and about what it was like to go return to Afghanistan and and reconstruct that site. It was a very hopeful image. And I won first prize and started my education at the Olimov College of Art, in Dushanbe.

The professors there were post-socialist, and very serious. Everything they did was very observational, very technical, very academic. I was the youngest student in that college – and I had a great time. I was introduced to Tajik artists, to Russian artists, and my world started to slowly expand. I told myself, “There was no way I could be anybody else except an artist.”

[Art school] for me was about having a critical lens. Anyone could be a self-taught artist, but for me, it was important to be in a community of artists where I could think critically and academically. It’s not just about the work – I wanted to challenge myself and ask, “Who am I? Why am I doing things the way I do things? Can other people see things in my work that I’m not seeing?” I needed that push towards a more honest approach and self-reflection.

At Yale, we had these things called “pit crits” – if you look this up online you’ll find that a lot of artists have spoken about it. Pit crits are very intense. Every week, two artists would showcase their work, just whatever they have done so far, and all the professors and students from other departments would show up and critique them over the next hour or two. What is the work telling us? How are we reading it? How do we feel about it? Is it making us uncomfortable? What’s the history of it? What are the social, cultural and political implications? We had to read into what their art was trying to do.

It’s hard not to take criticism personally. That’s the other thing I have learnt – to tell myself, “I’m not going to cry, it’s okay!” But you need to as an artist find out what is it others can see, and what they can’t see about your work. Pit crits are a space of questions. It’s a very rich sort of place to be in, to learn about one another’s practice.

Diversity is something that is still lacking in many art institutions. I sometimes wished there had been more artists like me in my department so we could share our experiences and backgrounds and ideas about our work. But this has been changing at Yale in the last couple of years. It was mind-blowing to have individual studio critiques with Chitra Ganesh and Rina Banerjee, for instance, and to have them critique my work. I felt like I had an amazing umbrella of support. My world just opened and I realised I wasn’t alone, that I was doing the right thing.

You’re more widely known as a textile artist these days, even though you started off with painting as a medium. Would it be right to say that your time at Yale was instrumental to that transition?

Yes. [Up to that point] my art training had been very Western. But Yale gave me the freedom to be open, to question the hierarchies of what is fine art. Being here for two years allowed me to experiment with so many materials. I wondered why I kept painting patterns [from cloth] instead of using those fabrics that I was trying to paint directly in my art. I really began to question the material and the material in relation to myself and to my history. “Why am I painting? Do I have to continue painting? Why am I ingrained to the idea that art and painting should only be on canvas?” And I realised this was why I always had such a hard battle with painting – because the language of painting was difficult for me to make personal, to really make it mine.

When I grew up, I wasn’t given a brush or paints – they were too expensive. I only picked up painting when I was around 14 years old. So the only material I had access to growing up was fabrics. My mother and grandmother had taught me how to sew. Fabric is woven into my childhood experience but I kept ignoring it because I thought it wasn’t as valuable enough of a craft to incorporate into my practice. Because the idea that “this is what art should be – which is painting” has been something that was systematically imposed on us. I realised that my language, my material – fabric – had always been with me, but I never had the time to really be with it. Once I realised this, my world became very expanded. I became much closer to myself and who I was as an artist, and with what I’m doing.

When I start making objects around fabric, I noticed that people had the tendency to touch them for some reason. It felt so abnormal to me at first, because you would never do that to a painting – touch it without permission.

But fabric is so soft, so seductive and inviting. It’s a material that carries memory, scent, and it’s so fragile yet tactile at the same time. You don’t have much control over it, so you have to let it go, of what it can do.

What was it like to graduate during the pandemic?

When the pandemic happened, everything moved online. There were no pit crits in the first year, no physical connection or physical conversations. Nobody knew what was going to happen and we just took the tools that were available to us and tried to carry on. People started doing video work, or sound art, or writing poetry. Things became more diaristic. It wasn’t so much about creating objects anymore, but thinking of objects through a different language of art.

I already had a studio near my place, so having access to my objects and materials wasn’t difficult, but I really missed having my colleagues visit my studio and my work. I found myself in a place where suddenly, I had to critique my own work. It was a pause, but the thing that I learnt the most was to be patient, and to be grateful for whatever small access to my art that I had. I just had to be patient and keep going.

Being in isolation also inspired me to create new work. From my first solo show at T293 Gallery (“Bazaar, A Recollection of Home”) to “Mirrors and Faces” – those were all works that came out of the pandemic. Being in isolation really helped me sit with myself and sit with my memories and sit with whatever sources I had as an artist and kind of be with myself, be with my space more. It really enriched the way I thought materials, because there were no other distractions. These were the only objects I could have conversations with every day when I woke up.

Could you walk us through the creation of one of your textile pieces?

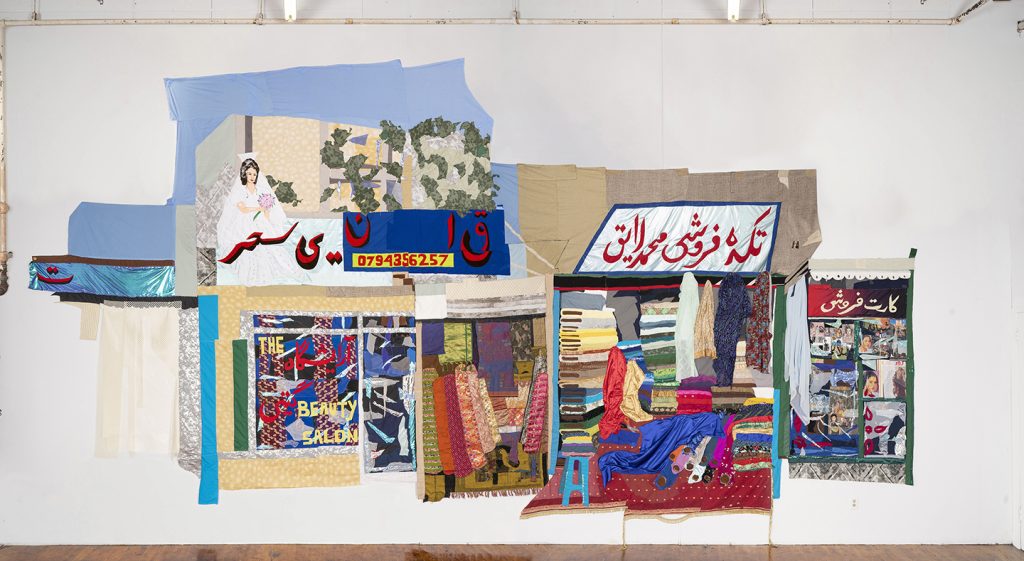

“Bazaar” is an example that I’m very proud of. It took me a couple of months to make, right after I graduated. It’s a panoramic piece that I did from memory. I wanted to draw the spaces I grew up with in Afghanistan, all the shops from my childhood side-by-side – fabric shops, tailors, beauty salons. I wanted to create an immersive view of what being at the bazaar was like, how a person’s body should navigate it, going backwards and forwards continuously, without a real start or ending.

Whenever I start a new textile series or story, I tend to go straight to drawing. So drawing is my foundational space with which to think, to bring my memories freely on paper. Those drawings are plain black-and-white drawings – colour only comes in when I’m choosing the fabrics. I redraw the sections in a larger scale on ground paper, and then I use appliqué, from quilting, to cut the fabric into different shapes before sewing them together.

When you paint with canvas, the frame is usually the first thing you see, because you paint inside the frame. But when I put the fabrics together, you don’t get a full image because there’s no frame. The edges are in a sense, very free. They’re amalgamations of different images that make a whole. The whole then becomes its own fragment. And I’m so into that. [laughs] It makes me so happy to think that the work is breaking out of the structure that I’m used to, breaking out of canvas, breaking out of the frame, just doing its own thing. Fabric does so much.

“Bazaar” was a very large piece. I actually never got the chance to see it in person, on a wall in front of me. Because I made it during the pandemic, I had to put it all together on the ground before shipping it off to Rome. But people keep sharing pictures of it, and what their experiences have been walking around it [in the gallery]. The idea that it’s now a travelling bazaar – that my collective memories are now travelling around – is so amazing and beautiful to me.

The work I did for Cooper Cole (“Mirrors and Faces”) were in comparison, fantastical and surreal…very dreamlike. This time, I did the drawings in colour because I wanted the drawings to be an exact imitation of the fabric. Artists should sometimes be free to experiment but I was stubborn with this series for some reason. There was an element of control and obsession that I was chasing – but that’s okay. I wanted to match my drawings to the fabric, and keep a very honest approach to texture and shape and colour in those drawings – which was really difficult to do. I was so happy when it happened. Even the textile pieces ended up having a drawing-like quality to them.

I’ve noticed a tonal shift from your earlier painting work – like “The Wind-up Dolls of Kabul” and “Shaharra” – from something that is quite politically-charged, tense and urgent to the more communal and private refrain that runs through your textile pieces. “Bahar, Beauty Parlour” and “Wandering Amidst the Colours” almost seem to reference elements of street photography. I feel like I’m walking through the streets of a city looking into shop windows, looking at what people are doing and eating. When we do see individuals, they’re looking away from the ‘camera’, relaxed and reposed. But for the most part there’s a very strong sense of a group. There’s safety in numbers but in that safety there’s also strength.

Interesting point. I do when I look back at my older work see how its symbols and figures can feel that way. The political message is very overt and immediate.

Perhaps it’s where I started working with fabric that this changed. The touch of fabric is different from a brush. There’s a different sense of agency.

At the same time I started doing figurative work with fabric I was also thinking and playing around the idea of the gaze. Women gazing at the viewer, women’s bodies confronting the viewer. I looked at Kerry James Marshall’s paintings, and the way he depicted bold and frontal poses using elements from art history. And I thought, “What if I started using these gestures in my portraits and see how my viewers will react? Will they come closer and touch the fabric or step back?”

And that’s what happened when I did the “Bahar, Beauty Parlour” series. It depicts a group of women chatting with each other indoors, and another woman and a military guard standing outside the salon. These are the only two people who are gazing at the viewer. And people [at the exhibition] stepped back. They didn’t start touching my fabric. It was amazing that fabric can make you act in different ways, depending on how you treat it, what sort of tricks you use. Finding its own power and fragility.

The more I developed as a political artist, or an artist of the people, the more I became interested in what is the ordinary. Why not the ordinary? Why can’t we just focus on the ordinary life? I now find it much more important to bring in contemporary voices of Afghan women, what they’re doing, what sort of fashion they’re wearing, rather than putting her in a box of politically-charged stereotypes like maybe I used to do.

What do you make of the expectation that ‘artists of colour’, or ‘women artists’ or ‘immigrant artists’ should be expected to make work that looks a certain way, or have a responsibility to talk about certain issues? We’re often asked “What does it mean to be a diasporic artist” or “What is it like to be part of THE diaspora” as though there’s a single shared experience.

“Wandering Amidst the Colours” was a pandemic work I made wandering New York City in search of diasporic Afghan communities – restaurants, fabric shops and things that were familiar to my own background and home. It was important to me to connect to make work about the Afghan diaspora, and to connect with these communities. But although, yes – I have experiences as an immigrant, or as a refugee, or as part of the diaspora, my world is too big to be categorised as just one thing. I wanted to not allow myself to be pigeonholed, but also not be tokenistic.

POC and diaspora artists became a very hot thing during the pandemic, because of the Trump era and Black Lives Matter. We’ve been here for centuries and this entire country is built on immigrants but suddenly people were asking, “Where are all the artists of colour?” Where were you? We became this wanted commodity and I had to be careful about who I was showing my work to. I had so many opportunities at my door, which was amazing in a way, but also dangerous, because identity was selling. I had to move a little slower and choose wisely. I looked at the history of the galleries who contacted me, whether they’d represented POC and other diasporic artists – or was it just going to be just me, representing everyone. It’s how the art world plays you, in a way. It makes their job easier to put you in a box.

Could you tell us more about what you’re working on next?

I have a new show coming up in London at the Union Pacific Gallery that is literally dedicated to my mom and dad. I’m continuing to revisit childhood memories but in the context of my parents’ relationship to me and to the spaces they were refugees in.

Our family was separated because of the war. My father was displaced in Europe, where he was seeking asylum for 9 years and doing cash jobs in refugee camps. The rest of us – my mom and four children – were in central Asia, migrating from place to place. There are two different individuals experiencing the diasporic experience in two different ways, and it’s a huge gap I’m only just waking up to – why they were even separated to begin with, and how it affects me as an artist today. Because I’m very close with my mother and the community she shared with me growing up, which comprised of all women. But my paternal side is like a fantastical image to me.

A big focus of this work was the objects of communication they used to keep in touch with, which was photography and letters. It was the only technology they had access to at the time. It was fascinating to go back to the images they would send each other. My mom would pose in these post-Russian, fully furnished rooms we used to live in, wearing very elegant and beautiful dresses. My dad would send photos from places like Norway and Denmark, where he would pose behind tulips, in a park – everything so green and peaceful. Seeing his images created my own fantasy of a European dream, like an American dream.

My dad sent them to us as a promise that he would someday bring his family to this land. But my mom would send her photos to show she’s already doing fine, she had created a new reality of a home in Tajikistan, and she owned it. But the objects and furniture didn’t relate to her cultural background of Afghanistan at all. This is another way immigrants try to define what home is, and what they could feel comfortable in the spaces that don’t belong to them. They’re in foreign lands but they somehow need to find a sort of belonging or safety and security in the aesthetics that play around them.

And these stories are still alive. When the evacuation happened in Afghanistan this year so many families got separated again. Many male members of my family became refugees in the United States or Europe, but their wives and children would be somewhere else. And I remember, we went through the same thing growing up. That’s why I try to tell these stories, but not be shy and embarrassed about putting myself in this vulnerable position – which is so personal. But because it’s so personal it might speak to other families and other communities who are going through the same thing. Home has so many meanings to us. Working around topics like diaspora and displacement – there are so many perspectives you can fill it with. So many stories. And this is my story, a way to reconcile with my past. Re-remembering and giving it a space to speak and have a conversation. History is just repeating itself, just in a different time with different people.