The Power of Art Amidst Tragedy

My story with art started a long time ago, way before I was born, in a millennia long past. I don’t know the exact day it started, but I do know that somewhere along its journey there were Syrian hands making Ancient Roman pottery, an architect designing Palmyra’s great arches and columns, a sculptor shaping young Syrian men and women with curly hair.

My story with art is the story of ancient mosaics and ceramics with the brightest colours, dug up centuries later from under the soil of my city. With passing time, my story with art became ancient temples and synagogues and churches and mosques, the belt of Mary and the intricate patterns on the walls of the Umayyad Mosque. Silver jewelry, fabrics spun on looms, Aleppine qudud sung in dulcet voices. My story with art is the story of Syrian art, a tale as old as time because Syrians have always been creating. Through freedom, prosperity, war, occupation, Syrians never stopped creating.

It was only a few days after the Syrian regime’s forces fired on unarmed protestors in the city of Dara’a that Syrian singer Sameh Choukair released his song, Ya Heef. “How could you shoot unarmed people?” he sang:

“How could you arrest children the age of flowers?

How could you hurt your own people?”

He poured his pain and worry for his people into his lyrics, and his song echoed across communities. When I listen to Ya Heef (‘O Shame’), I’m transported back to 2011 and the fragile feelings of the time. My fear upon hearing protests and police gunfire from my house. My awe and pride at the bravery of the young protestors who would seek refuge from police brutality in our tiny building. Even a decade later, his words hold the same sentiments of hope and pain for Syrians. They’re a remembrance of the innocent lives we lost and our struggles for freedom. More importantly, they’re a testament to the connection of art to our cause.

As the regime’s violence intensified, as Syria turned into a playground for terrorism and brutality, so did Syrian people turn to art. Songs after songs were released — sad songs and upbeat songs, songs full of hope and pain. Syrians danced in the streets, wrote poetry and chants, painted and crafted and created. When we were losing hope, our art was there to lift us up again. When the world forgot about us, our art was how we expressed our anguish. Art was — and still is — our refuge and our way of expression.

In my city of Homs, protestors were often seen carrying a cardboard miniature of the New Clock Tower — a small, off-white clock tower with black stripes that became an icon of Homs’s revolutionary spirit. From a distance, a cardboard miniature might appear insignificant. But it meant someone was there, cutting pieces of cardboard, painting them the colours of the Clock and putting them all together with care. Every creation we made — no matter how small — mattered.

Even today, after over 10 years of shelling and war, with millions and millions of displaced Syrians and countless in the regime’s prisons, we are creating. Somewhere on a forgotten side of YouTube, there are videos of artists painting on tents in refugee camps, kids putting on plays, a displaced Syrian man inking the neatest calligraphy into blank pages, filling up his time with holy words. Idlib’s broken walls have become a canvas for graffiti artists who paint messages of hope for Syrians, and messages of solidarity for people across the world.

Somehow, after everything we’ve been through, we’re still creating.

I’m lucky when it comes to my experience as a Syrian. My losses are nothing compared to what others have been through. Still, there’s something exhausting about being Syrian. The things we’ve witnessed and lost are unreal.

Then there’s exile.

Being miles and miles away from our loved ones. Every day, I have to come to terms with the fact that I’ll never be able to make up for all the time I’ve lost, all the days and years that slipped like sand between my fingers, days I could’ve spent with my loved ones instead of being oceans away. Exile is a constant thing. You don’t just get exiled once; you get exiled every day of your life, every time you wake up far away from everything that matters to you.

Exile feels different to everyone, but for me it’s a looming presence, this sense of loneliness and strangeness that follows me wherever I go. Most days I can ignore it, but sometimes the weight of it starts to crush me from the inside. There are nights I spend awake, thinking about all the things I missed, all the things I’ll miss. How many more times will I be able to see my grandparents again in my life? Will it ever be enough? How many more times will I get to stay up late laughing with my cousins? Will my family ever be reunited without someone missing? At other times it’s the smallest things that hurt, like knowing I’ll never pick olives or sleep under the stars in our farm ever again.

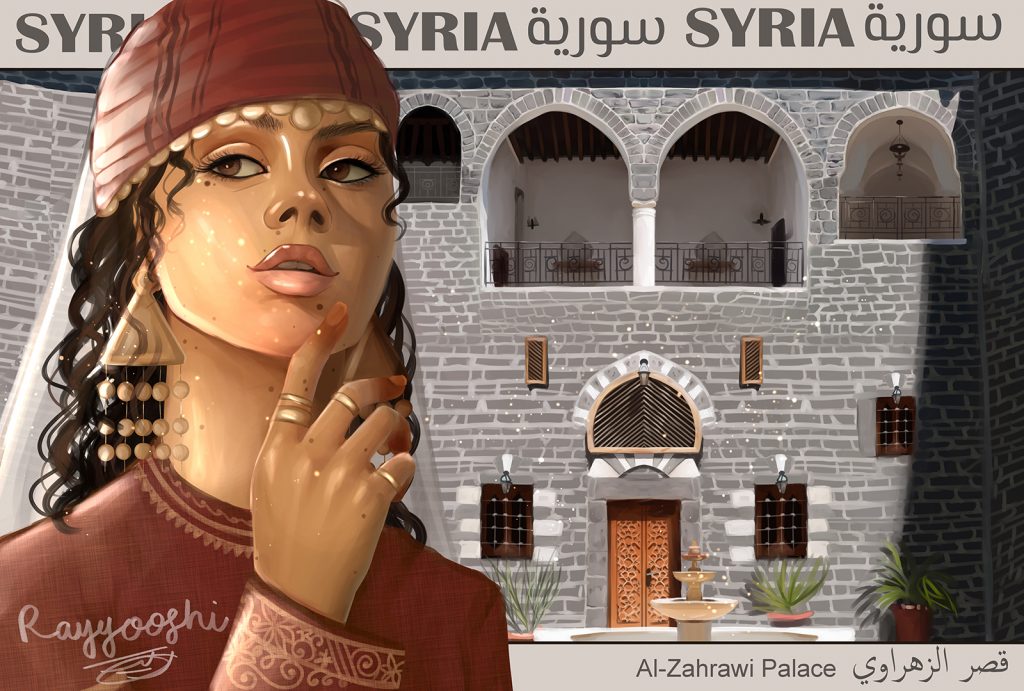

Syrian art is my solace, my healing. It’s what makes exile a little easier. It’s what makes distance a little more bearable — a little less long, even. There’s something soothing and self-indulgent about a morning spent painting a traditional Syrian house while listening to Arabic music. Drawing Syrian landmarks and traditional clothes, Syrian girls that look like me. These moments mean everything to me. In a way, I’m making up for all the time I’ve lost and all the things I can’t do anymore. For a small moment I can return to the sprawling fields of al-Rastan, swim in the Asi River, and lounge under the grape vines in our farm.

My art is how I reconcile with my Syrianness and all the pain and loss that come with it. There are times I wish my ancestors hadn’t settled there, that we hadn’t ended up in the land piece labelled ‘Syria’ on the broken post-WWI map. I wonder if that would have spared me some of the pain I’ve experienced.

As a Syrian artist though, my relationship with my identity changes. I’m no longer just ‘Syrian’ — the nationality accompanied by destroyed homes and exile and loved ones gone missing. I’m a Syrian artist, part of a group of people who are immensely skilled, who have been brave and strong against all kinds of oppression. People who have refused to stop creating. People with hearts of gold and hands of gold and voices of gold.

My story with art is full of history and hope, pain and healing. It’s the story of Syrian art and Syria’s artists. Every time I see Syrians creating, whether it is music or paintings or poetry or plays, it just fills me with so much joy. I’m so grateful to be part of this community of resilience. I’m proud of us and everything we’ve created.

I owe Syrian artists so much. The world owes Syrian artists so much. Their stories teach us that art is an inseparable part of resistance and hope. Because as long as we’re creating, it means we’re still alive and here and refusing to let our oppressors break us. It’s like getting a piece of my soul back, like finally coming home.

Raida Farzat is a young artist born in Homs, Syria. She loves drawing and painting, both digitally and traditionally. Her main sources of inspiration are her memories from Syria, old Syrian post stamps, and other Syrian artists. You can find her on Instagram at @rayyooshi